A Brief Look at the Unaccompanied Youth of Europe

Who is an unaccompanied child?The Guidelines on Policies and Procedures in Dealing with Unaccompanied Children Seeking Asylum, Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Geneva, February 1997 (pg. 1) defines an unaccompanied child as “An unaccompanied child is a person who is under the age of eighteen, unless, under the law applicable to the child, majority is, attained earlier and who is separated from both parents and is not being cared for by an adult who by law or custom has responsibility to do so.”

Because terminology changes over time and varies across organisations and geographies, for the purposes of the work of the Mobilised for Unaccompanied Minors (M.U.M.) Network, we use the terms unaccompanied refugee children and youth, unaccompanied minors (UAM), UASC (an acronym used both for "unaccompanied asylum-seeking children" and "unaccompanied and separated children"), and unaccompanied youth all interchangeably.

We must be cautious however in our use of terms vs. labels. We are talking about children and youth who are without an adult family member at this time. We must not allow their status as an unaccompanied child to become their identity. Instead we allow it to be an indicator to us of a level of need that may exist in this season. While these children are in the process of seeking asylum and are traveling alone, they are highly vulnerable to predators, traffickers, smugglers and radical extremists. It is also likely that they currently are without the material resources they need to have a healthy, safe, stable life and may be losing hope for their future.

Why are these children “on the move”?

According to the High Commissioner’s Dialogue on Protection Challenges, Children on the Move, 28 November 2016 (pg. 6): “Studies show that armed conflict and violence are among the most frequent drivers of displacement of children, but children face many types of violations of their fundamental rights. The refugee definition therefore: …must be interpreted in an age- and gender-sensitive manner, taking into account the particular motives for, and forms and manifestations of, persecution experienced by children. Persecution of kin; under-age recruitment; trafficking of children for prostitution; and sexual exploitation or subjection to female genital mutilation, are some of the child-specific forms and manifestations of persecution… Child-specific forms of persecution are often interconnected with other factors, including the loss of parents to war or disease, acute poverty and food insecurity, and lack of educational and economic opportunity. The particular discrimination and barriers stateless children encounter make them especially vulnerable to forced displacement, trafficking and the worst forms of child labour.”

Why would parents send their children alone?

When children move alone it is often because the family can only afford to send one child, not necessarily the eldest, to seek protection elsewhere. This tendency may be bolstered by a “culture of migration” that has developed over time, backed by a strong diaspora, and sometimes by misconceptions about immigration and refugee policies of destination countries. Families have usually invested heavily in their child’s journey and for these children, failure is not an option; the responsibility to reach the intended country or region and to repay their family’s debt weighs heavily on them.Children can also become separated from their parent(s) or suffer the death of their parent(s) during their forced displacement.

- High Commissioner’s Dialogue on Protection Challenges, Children on the Move, 28 November 2016, pg. 6

As borders close and people flows change, where are the children now?

The most recent data is from January through September of 2017. While the numbers of arrivals of asylum-seekers has decreased, the countries they arrive to are still also trying to manage the processing of and services for those who arrived in 2015 and 2016. This has created a challenge of over-filled shelters and slow processing time for asylum applications. As a result, many unaccompanied youth choose to try to exist outside of the system, which often puts them into increased danger of being trafficked or exposed to hazardous travel conditions. Additionally, for a variety of reasons, it is challenging to gather accurate data to assess their current situations across Europe.

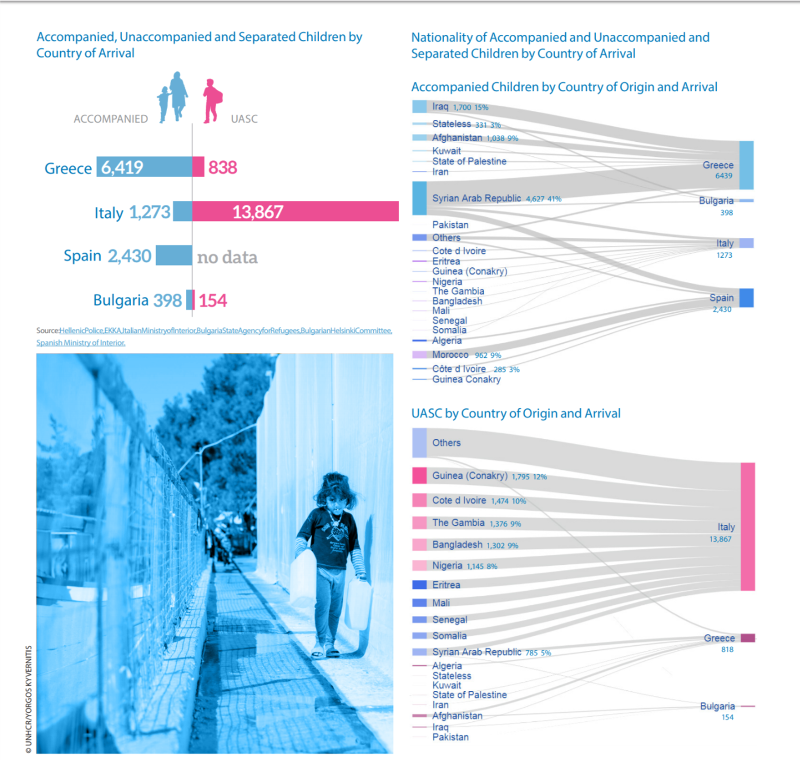

This chart, from UNHCR, UNICEF and IOM's report: Refugee and Migrant Children in Europe, shares some of what is known of new arrivals for January through September 2017: